Morbid Mobilities by Tsvetelina Hristova

LOCKDOWN THEORY #33

Epidemics spread by parasitizing on already established flows of mobility of people and new crises parasite on crises that have settled to be the normality. In the weeks after COVID-19 reached EU, the epidemic has accelerated the conjuncture of existing modes of exploitation, extraction, and exclusion. Kim Moody points out in a recent piece that the link between the spread of COVID-19 and transnational supply chains might be a lot more significant than what is immediately apparent from epidemiological models.[1] This invisibilized dependency between the spread of the virus and the mobility of capital and labour is only one way in which the current rapidly developing COVID-19 crisis is not just a health emergency but much more than this, it is a problem of labour. Labour, and in particular migrant labour, has become the central subject of this crisis - monitored, contained, and stirred into “essential” mobilities.

Vectors of Contagion

The path of initial infection in Bulgaria remains unclear because the first cases were already cases of community transmission. But there is persistent suspicion that Bulgarian migrant workers in Italy came back home for holidays and brought the virus to the former industrial towns of Gabrovo and Pleven. Like many towns in the country where key industries were dismantled, privatized, and liquidated after 1989, these two regions of Bulgaria are among the ones with significant demographic decrease and out-migration to the capital or other EU countries. In the last 30 years out-migration has become a major source of cash flows back to the country. Migrant workers have consistently contributed significantly larger amounts to the economy than foreign direct investments. It is not an exaggeration to say that the livelihood of whole families, and in some cases whole townships, is sustained through the cash flows coming from migrant workers.

At the same time, in its history of migrant labour regimes, the EU has consistently restricted and made conditional the access of workers from its eastern peripheries to social security, benefits, and healthcare protection. This has lead to a rift in the geography of production and social reproduction in the Union that forces Eeastern European migrants to separate the spaces of labour from the spaces of social reproduction. Tasks of sustaining health, social networks, and social security are relegated to the home country and, more specifically, to the household, which, in the context of eroding social protection from the state becomes the central institution for social reproduction.[2] People come back home to see their family but also to get dental and medical care, to buy medicines (often for other migrants who couldn’t travel back home too). This means that migratory patterns of Eastern European migrants are part of vital infrastructures for sustaining the precarious livelihoods of impoverished working classes in the region. Now they have turned into vectors of contagion, underscoring even more the dependency of Eastern Europe on emigrant labour and the ease with which the West dispenses of migrant workers.

In the days since the virus landed in the EU hundreds of thousands of Bulgarian migrant workers have returned home after quarantine measures lead to labour market stagnation and efforts to restrict seasonal migrant work and discourage precarious and unemployed migrants from seeking social support.[3] Pushed back into a healthcare system that will most certainly not be able to deal with a pandemic, returning migrants are now the focus of punitive and surveillance measures in Bulgaria and the Eastern European region.

Epidemiologies of Migration

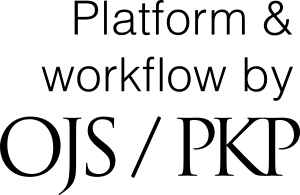

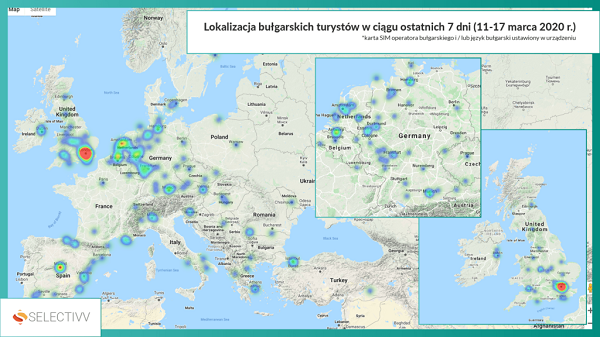

In March the Polish digital marketing company Selectivv, which has an office in Sofia, published their own study on the movement of Bulgarian and Polish migrants in the EU during the pandemic. The company used this data to create a map tracking their movements in the period between March 11-17, the early days of infections in Eastern Europe - where they have been in Western Europe and where they returned in their own countries - a sort of unofficial epidemiological surveillance map tracing the potential spread of the virus. It combined geolocation tracking and profiling technology used specifically for targeting migrant diasporas, drawing on mobility data and consumer patterns. Selectivv explains this technology on their website by providing their own definition of a migrant for the purposes of profiling in the following way:

In this research we assumed that “a person from Ukraine living in Poland” is one who has a SIM card of the Polish operator, but has the Russian or Ukrainian language set on the phone and at least once has been in Ukraine during 2018 and/or changed during this time the SIM-card of the Ukrainian operator.[4]

Visualization of the location of Bulgarians in EU (above) and where they came back to in Bulgaria (below) from the website of Selectivv. Available at: https://selectivv.com/en/overall-picture-of-covid-19-situation-based-on-data-from-mobile.

This data assembled by the company was voluntarily provided by the Sofia office to the Ministry of Interior for the purposes of tracking returning migrants and ensuring they are quarantined. The ease with which migrants are turned from consumer subjects of marketing profiling into dangerous subjects of surveillance and control is both striking and unsurprising. The present economies of valorization of information that have accelerated the collection of data by corporations like Google, Facebook, Amazon and many others are part of a long and varied history of archives, registers, and measurements used for control and exploitation. As Mark Andrejevic argues, the type of data collected and the focus of its analysis in nineteenth century labour management and twenty-first century marketing are more similar than we think.[5]

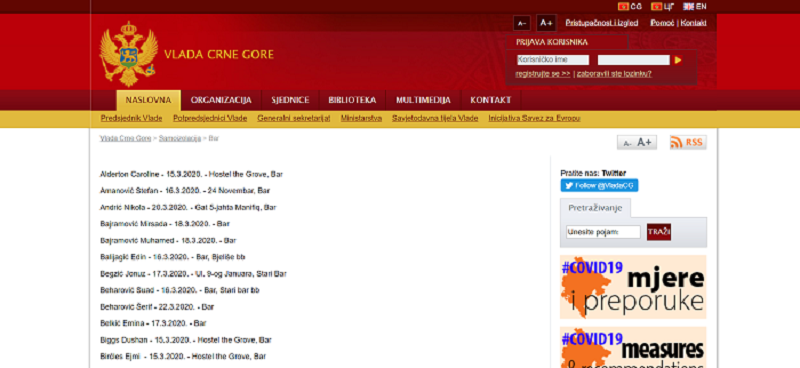

However, there are a number of seemingly discordant measures for surveillance and containment in Bulgaria and other Eastern European countries that show that issues of privacy and surveillance are not necessarily and exclusively linked to the increased use of big data and digital technology, and, second, that there is a stark and racially motivated contrast in the different measures enforced on different populations. The first tendency, the use of a sort of citizen policing, in the sense of mobilizing citizens to police each other, leads to the proliferation of lists, reports, and mutual policing. In one such example, the government of Montenegro uploaded a list on its website with the names and addresses of people who need to self-isolate. There was a similar publicly available database, or, rather, a list of people in self-isolation published by the authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. After an intervention from the Data Protection Agency in Bosnia and Herzegovina the lists were taken down but the ones in Montenegro remain. This solution shows a different side to the use of surveillance and epidemiological management, which draws on the spectacle of transparency, rather than the panopticon of big data collection.

Part of the list of persons in isolation on the website of the Government of Montenegro (screenshot by the author).

An analogical citizen police approach was adopted in Bulgaria, where people had started filing reports with authorities about neighbours or relatives who have returned from abroad and did not self-isolate. Letters (sic!) are being sent to the crisis headquarters that manage the national response, in which people from small towns and villages report on neighbours returning from abroad and not self-isolating.[6] This popular policing of returning migrants is motivated by the growing anxieties of Bulgarians that the healthcare system will not be able to handle a full-blown epidemic and that widespread lockdown measures will lead to a catastrophic economic crisis. There is some kind of moral austerity in the way people embrace self-discipline and police others in the hope that they can just bear it through and make it last shorter.

Drone Camps

While there is general suspicion and policing of returning migrants, Roma neighbourhoods have been the objects of a different type of measures in Bulgaria, but also in Slovakia and Romania. In Bulgaria, some cities have opted to seal off Roma neighbourhoods putting police or army officers to monitor and control who comes in and goes out. These measures have been rationalized by the authorities in two ways - that there is a high number of returning migrants among the Roma, and that they don’t observe proper hygiene and discipline, the latter being a classic anti-Roma racist argument. In the Roma neighbourhood of Bourgas the already sealed off inhabitants were also subjected to another control measure - the use of a drone with an infrared camera to monitor the body temperature of people there. The drone was developed by a private company and made available to the Ministry of Interior, so it is not a medically motivated measure, but clearly one of control. After identifying four cases of fever the day after the drone was initially deployed, it was reported that the data is used to monitor the movements of people who are quarantined rather than identify new cases.[7] While the drones don’t seem to have efficient role in preventing the spread and easing the access to healthcare for the Roma, they do efficiently deploy the militarized aesthetics of othering and depersonalized, dehumanized targets of intervention.

Infrared image from the Roma neighbourhood in Bourgas. Source: https://dariknews.bg/regioni/burgas/v-burgas-dron-shte-meri-temperaturata-na-naselenieto-v-getata-snimkivideo-2217811.

Drones are also used in the Roma neighbourhoods to play recorded warnings and instructions. This control at a distance is reserved exclusively for the Roma and is not a sign of economy of governmentality, not an attempt of non-intrusiveness but, on the contrary, a clear sign of segregation and encampment of minorities, kept isolated and separate from the rest of the population, similarly to the leper colonies. Faine Greenwood calls this the “shout drone” - alienating “technology of distance” that is especially problematic when deployed on marginalized and vulnerable populations.[8] After making a show of sealing off neighbourhoods with no clear healthcare plan, testing in Roma neighbourhoods was only done in the second half of April by which time 50% of the tested were positive. Instead of rethinking the adequacy of the preventive and containment measures, the response was further scaling up of the sealing off of ethnic neighbourhoods.

Essential Disposables

According to the Bulgarian prime-minister, the number of Bulgarians who returned from abroad since the beginning of March is about 200,000 people (for comparison, the total population of Bulgaria is about seven million). And the problem is that for these people, as well as for a large part of the non-migrant population, there is no social or economic security in the context of increasing unemployment and economic stagnation. The government has voted a limited number of measures that encourage employers to keep their current workers, offering to provide 60% of the salary of workers who would otherwise be laid off. But this would only apply to a very narrow definition of employment, non-precarious workers on regular non-casual contracts. Returning migrant workers would also not be eligible for this kind of support or for unemployment benefits.

At present, there is a growing void in policies of social reproduction and, essentially, the basic reproduction of labour and life. And this void adds to a longstanding crisis of social reproduction in the EU, in which migration from Eastern Europe has had a double role. On the one hand, the issue of access to social benefits has been a matter of disagreement between member states and states in Western Europe have for long been trying to limit the access of Eastern European migrants to social benefits and protection, feeding the discourse of “benefit tourists” - people who migrate in the West and then take advantage of the “generous” social security systems there. On the other hand, Eastern European migrants have been essential in sustaining the commodified social reproduction services in the West by providing services as care workers, domestic workers, and agricultural workers.

As borders between EU countries close now and migrants are returning home, these reproductive services in the West are experiencing lack of migrant workers. At the end of last month, Austria and the U.K. both sent charter flights to “fetch” temporary agricultural and care workers from Bulgaria, Romania, and Poland to fill in the gaps. As a result of the pressure of countries experiencing need for migrant labour, the EU issued recommendations for free mobility that include temporary agricultural workers and care workers in the “essential workers” occupations that should be allowed to move across borders during the COVID-19 pandemic.[9] The very notion of “essential workers” that crystalized in the time of the pandemic is sufficiently problematic. In the context of healthcare measures when the only guaranteed protection is social distancing, essential workers are the ones whose labour not only sustains the vitality of economies but also puts their own lives at risk. Given that the decision of what constitutes “essential occupations” is taken by capital and that most of this work is low-wage, it is hard to dismiss the realization that “essential labour” means “disposable lives.”

How does this work into existing cross-border inequalities in the EU? It creates a situation of impasse for workers in the East who don’t receive social and economic protection from their governments and are pushed to choose between precarious mobility with no clear guarantees for proper health protection abroad and imposed stasis and economic stagnation at home, which, in the case of Roma people, is also coupled with racialized encampment. These descending circles of death and exploitation involve multiple subjects of labour across the Union, as well as the constellation of supranational jurisdiction, national capital, and multinational supply chains of labour. One of the major unions in Bulgaria, Podkrepa, issued an open letter to the government demanding that either workers are not allowed to travel abroad and offered social protection in the country, or that Bulgaria demands of Germany, Austria and U.K. to retain the migrant workers and provide them with healthcare for the duration of the pandemic.[10] The rationale behind these demands is that continuing temporary migration in time of pandemic endangers the rest of the population back home.

In the current pandemic Eastern European migrant labour remains caught between being a dangerous vector of contagion and disposable life, between punitive measures and exploitation. And even so, there are different levels of exploitation and disposability, in which Roma remain consistently invisibilized, missing from the statements of unions. Is it possible to imagine organizing across these lines, workers in different countries, migrant labour, and the most marginalized and racialized without imposing a singular and homogenizing image upon these different experiences? This is the most pressing question in this pandemic, which does not affect us equally, as some claim, but highlights that the main contradiction for all, in their heterogeneous experiences, is capitalist economy versus life.

[1] Kim Moody, “How ‘Just-In-Time’ Capitalism Spread COVID-19: Trade Routes, Transmission, and International Solidarity,” Spectre Journal (April 8, 2020), https://spectrejournal.com/how-just-in-time-capitalism-spread-covid-19.

[2] See Raia Apostolova and Tsvetelina Hristova, “The Postsocialist Posted Worker: Social Reproduction and the Geography of Class Struggles,” in Migration and the Contested Politics of Justice: Europe and the Global Dimension, eds. Sandro Mezzadra and Giorgio Grappi (London and New York: Routledge, forthcoming). See also Miladina Monova, “‘We Don’t Have Work. We Just Grow a Little Tobacco’: Household Economy and Ritual Effervescence in a Macedonian Town,” in Economy and Ritual: Studies of Postsocialist Transformations, eds. Stephen Gudeman and Chris Hann (New York: Berghahn, 2015), 166-191, for an analysis of the increased economic importance of the household after 1989 in North Macedonia.

[3] Emilia Milcheva, “Стотици хиляди българи се върнаха заради коронавируса. Какво ще им предложи България?” [“Hundreds of Thousands of Bulgarians Returned Due to the Corona Virus. What Will Bulgaria Offer Them?”], Deutsche Welle Bulgaria (March 26, 2020), https://www.dw.com/bg/стотици-хиляди-българи-се-върнаха-заради-коронавируса-какво-ще-им-предложи-българия/a-52921930.

[4] Team Selectivv, “Do Ukrainians Build Their Future with Poland? The Latest Selectivv Study,” Selectivv.com (March 7, 2019), https://selectivv.com/en/czy-ukraincy-wiaza-swoja-przyszlosc-z-naszym-krajem-najnowsze-badanie-selectivv-2.

[5] Mark Andrejevic, iSpy: Surveillance and Power in the Interactive Era (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2007).

[6] Ivana Ivanova, “Ген. Мутафчийски: Получаваме сигнали за неспазване на карантината от наши сънародници” [“General Mutafchiisky: Signals Received by Compatriots for Quarantine Not Being Respected”], Eurocom.bg (March 7, 2020), https://eurocom.bg/new/gen-mutafchiyski-poluchavame-signali-za-nespazvane-na-karantinata-ot-nashi-snarodnitsi.

[7] Petya Mihova, “Дрон с термокамера засече 4-ма души с висока температура в Бургас” [“Thermal Drone Camera Caught Four People with High Temperature in Bourgas”], Bulgarian National Radio (March 21, 2020), https://bnr.bg/post/101244534/dronat-s-termokamera-zaseche-chetiri-dushi-s-visoka-temperatura.

[8] Faine Greenwood, “The Dawn of the Shout Drone,” Slate (April 16, 2020), https://slate.com/technology/2020/04/coronavirus-shout-drone-police-surveillance.html.

[9] The official recommendations are available at: Official Journal of the European Union, Vol. 63, C 102I (March 30, 2020), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:C:2020:102I:TOC.

[10] “Отворено писмо относно продължаващите пътувания на български работници към и от Западна Европа” [“Open Letter Regarding the Ongoing Travels of Bulgarian Workers to and from Western Europe”], KT Podkrepa (April 1, 2020), http://podkrepa.org/news/отворено-писмо-относно-продължаващи.

Tsvetelina Hristova is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Culture and Society, Western Sydney University. She is interested in issues of automation and digitalization and in tracing their political genealogy and implications.